By Carolina Chaimovich

Bruna Weichert had just settled into her new room in Los Angeles weeks after she graduated. She was ready for her first job interview, and looked forward to the year ahead.

Weichert, 23, moved from Dubai to Washington, D.C. to attend American University in 2013. She was studying film and media arts and looked forward to someday working in Hollywood.

She says she always knew working in the film industry would be trying and competitive, but she didn’t realize the biggest challenges she would face would not be related to the industry itself.

“People always said you have to work hard if you want to live the American dream, I just didn’t realize how hard, I really thought I’d be the one percent that makes it,” Weichert said.

She returned to Dubai three months later.

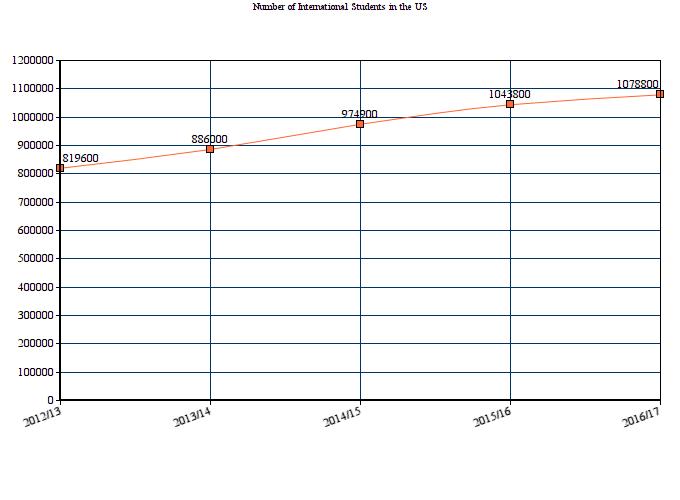

Bruna Weichert is one of approximately 886,000 international students who came to the United States in 2013 to receive an American education. International students who want to stay and work in the U.S. after graduation have the option of completing a year of Optional Practical Training (OPT).

OPT is an employment authorization that allows F-1 students to work in the United States in the area of their studies for 12 months or 24 months for students with degrees in the areas of math, science, technology and engineering.

“If you want to do OPT, there are so many deadlines. There is a deadline for applying, and a deadline of when you have to stop working, and a time when you’re not yet allowed to look for jobs and everything overlaps. It is so confusing and overwhelming,” Weichert said.

Weichert applied for OPT and immediately started to face difficulties. She had a hard time finding an apartment and was not able to buy a car because she had no credit score. She started to apply for jobs but often would get rejected because of her status. Weichert had three internships over the course of her undergraduate studies, is bilingual, and has a competitive CV.

She understood why possible employers would be skeptical of hiring her.

“They don’t know about OPT until an international person tells them about it. And with everything happening in the news, they are scared to hire us. They don’t know what’s going to happen next,” Weichert said.

Ever since President Donald Trump got elected, the idea of hiring Americans became highly talked about in the media and throughout the country and there have been attempts at establishing a Muslim travel ban, both of which could impact international students. However, there has not yet been any policy change specifically regarding OPT.

Weichert says although there is no change on paper, she feels the difference. During her job interviews, people would seem excited to work with her until they found out about her status. They would also ask her if she was a U.S. citizen, which is against the law.

When she finally found a job in her area, she was making minimum wage. International students are not allowed financial aid, and after eight semesters paying tens of thousands of dollars, she was not allowed to earn any of it back.

“It’s like we are set up to fail, I don’t know how they think anybody can succeed in this way, without financial support from their parents,” she said.

OPT allows people to stay in the country, but it doesn’t necessarily allow reentry. OPT is not a visa, it is a card where it says somebody is authorized to work in the country. Some people who are on OPT, choose to stay in the country for the 12 months because they are afraid they won’t be able to reenter the country.

Weichert says another challenge was thinking she would not be able to see her family for that amount of time. Home for her was in the Middle East, and that was a risk she was not willing to take.

Nick Xin, 22, a performing arts student from Beijing, China fears going through the same thing Weichert did. Xin chose to study in the U.S. because his field was very limited in China, and hopes to be able to further his career in the U.S. before returning home.

Xin and Weichert agree there is a lack of interest in knowing international students.

“People put us in a box, it’s like that’s all we are – international. But we’re humans, we have a story, motivations. If people truly took the time to get to know our stories, they’d have a hard time shipping us home,” Xin said.

They both agree there is great value to hiring competent international students because they bring different values, perspectives, have a different view of the world and are knowledgeable in more than one culture and frequently more than one language.

In September 2017, Weichert boarded a plane back to Dubai.

She felt her experience was not being valuable to her career and personal growth, and the struggles to find her path stopped being worthwhile.

“I just couldn’t do it anymore. I felt so lonely and couldn’t see the point anymore. It’s sad to think about how happy I thought I’d be, and look how it ended up.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.